Catching Fraud at the Wikimedia Foundation

15 Aug 2018Tags

Disclaimer - a lot of the values quoted below are ball-park figures given to estimate performance and results of this project. They are not to be confused as official Wikimedia Foundation Fundraising data.

Donations and fraud at WMF

Thanks to donors all over the globe supporting Wikipedia and her sister sites, the Wikimedia Foundation receives millions of donations in any given year. In the fiscal year 2016-17 WMF raised $91 million from over 6.1 million donations! Unfortunately the donations were not bereft of fraudulent transactions - transactions either made using stolen credit card details or made explicitly with the intent to harm WMF by causing monetary loss in the form of chargeback fees.

Frauds are usually anomalies when it comes to donations, but even assuming that frauds form only 1% of all transactions - that is still 61,000 transactions in the year 16-17. Taking into account that usually chargeback fees range from $15-$20 across various payment gateways, chargeback payments alone would cost WMF $1,220,000!

Fraud detection workflow

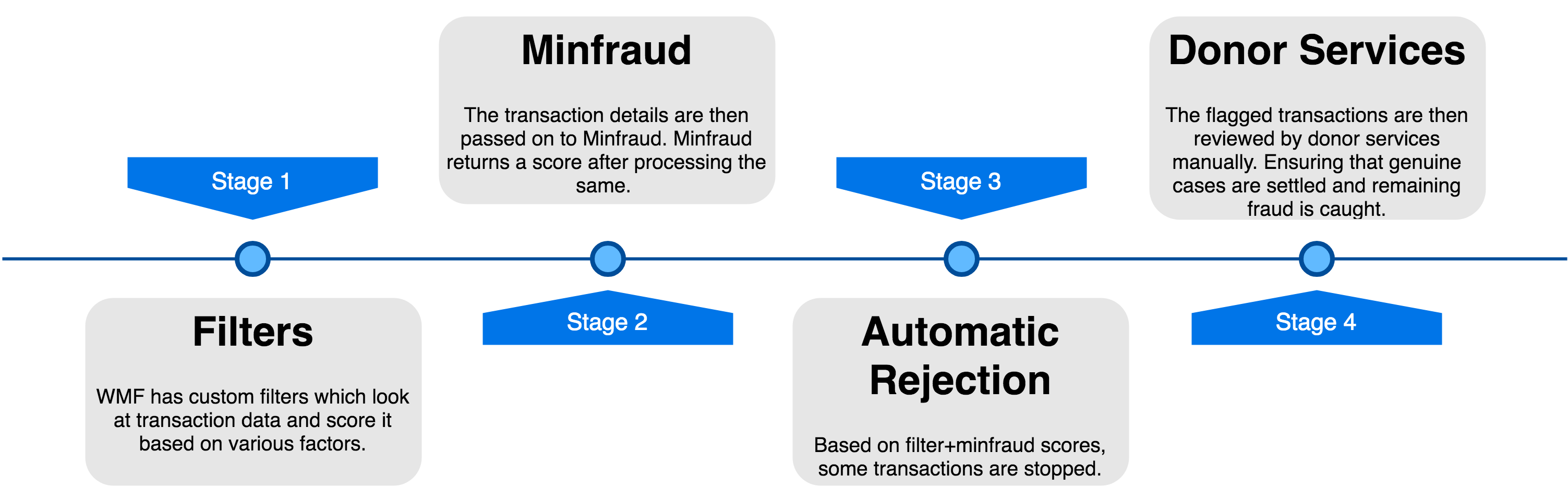

WMF Fundraising proactively works to make sure that fraudulent transactions are detected before they can be “successful”. The current workflow looks something like this -

While this approach worked just fine for a few years, statistics show that the performance of filters and Minfraud has continuously degraded over the years - with a lot of heavy lifting being done by donor services instead. Not only does this cost WMF money in the form of merchant refund fee but it also costs us in terms of man-hours spent looking at these transactions.

Research

In order to improve WMF’s automatic fraud-detection rates, we started experimenting with machine learning techniques for anomaly detection. After a few weeks of experiments, we decided to go forward and use ensemble techniques like random forests and gradient boosting to classify our transactions as fraud/genuine.

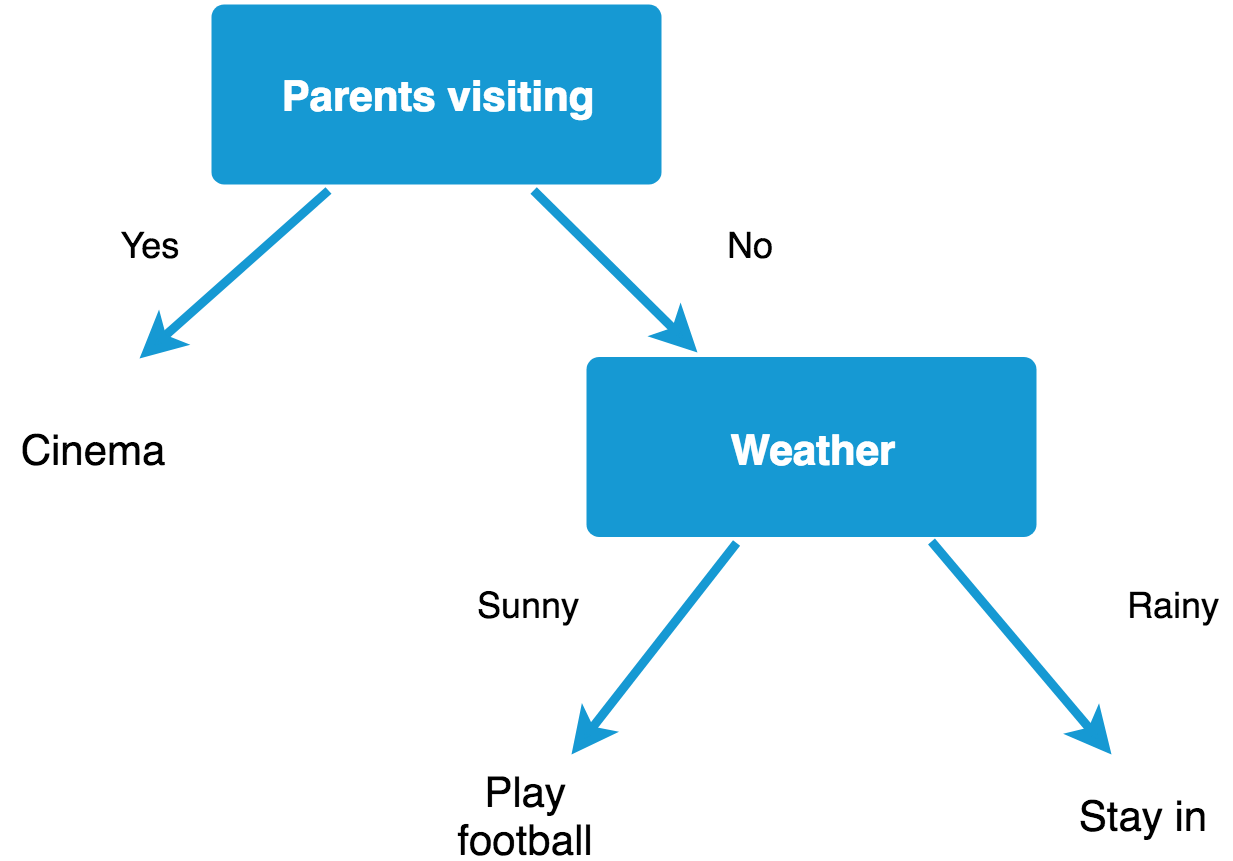

Both of these techniques involve the use of decision trees. Decision trees are very easy to visualize and intuitive to understand. Our classifiers make use of an ensemble of them - that is, several such trees are learned by our model by going through the data and the outputs of these are taken into account when making a final decision on how to classify the input.

A decision tree for my plans this weekend.

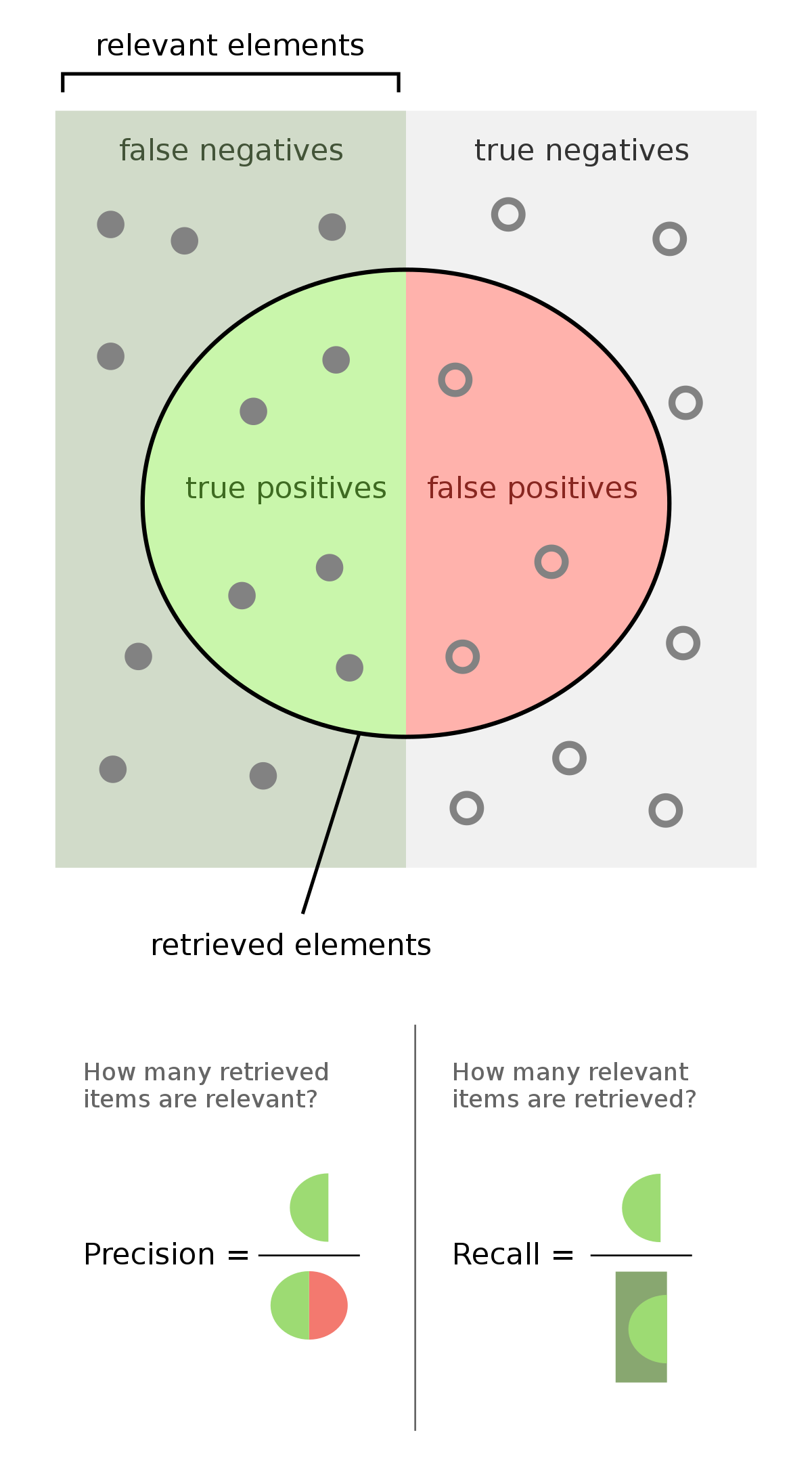

Our metrics for measuring model performance were twofold - precision and recall.

Precision in our case refers to “out of all the predictions made by the model, what percentage were actually fraudulent”. Recall refers to “out of all the fraudulent transactions, what percentage were correctly captured by our model”. Concentrating on only one is not enough, a healthy mixture of both is required. For example a model which just checks whether the name field is empty in a donation may be remarkably precise but will not cover a large spectrum of fraudulent transactions.

Precision and recall can be easily calculated by first calculating the following -

- True Positives (TP) - transactions which were marked fraud by the model and were actually fraud.

- False Positives (FP) - transactions which were marked fraud by the model and were actually genuine.

- False Negatives (FN) - transactions which were marked genuine by the model and were actually fraud.

Using these, precision and recall come out to be: Precision = TP / (TP + FP) and Recall = TP / (TP + FN).

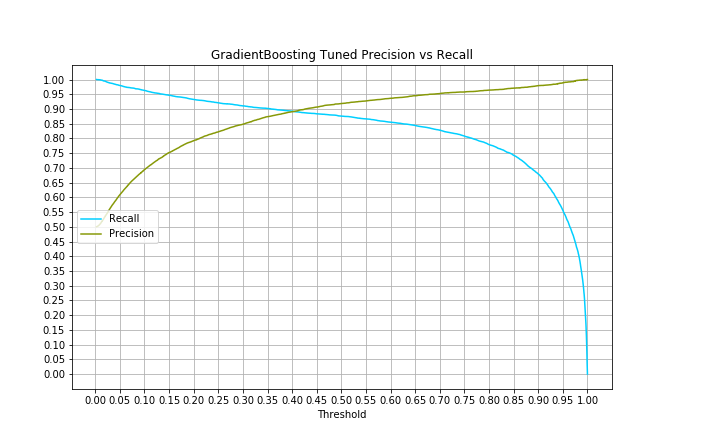

Ideally we want the values of precision and recall both to be as high as possible, however that is not always possible as an increase in one usually means a decrease in the other. We were able to capture the precision-recall tradeoffs and plot the following curve.

Results and comparisions

In a comparision of our classifier v/s the filters - we observed that statistically our classifier could’ve caused recall to increase about 50 points in the fiscal year 2017-2018 while maintaining the same 90%+ precision. A whopping 142% increase in the amount of fraud caught before a transaction is marked as complete, all the while maintaining the same percentage of false positives.

Benefits of the system include:

- could potentially save WMF tens of thousands of dollars in an year in the form of refund/chargeback fees.

- does not get out-dated like filters do - our classifiers learn to recognize trends in fraud as they evolve.

- easily maintainable - the underlying code and architecture need not be updated for the model to function effectively, we just need to re-train the model and swap it out every few months.

- numerous Donor Services man-hours are saved as the classifier only marks 35% of transactions incorrectly (fraud as genuine + genuine as fraud) as compared to our filters.

Proposed (and current) architecture

The classifier is to be made available to the WMF transaction flow as an intermediate RESTful web service. A working prototype of the API is ready and available here.

The API acts as a facade for a running instance of our classifier which effectively serves all requests.

However, the problem of generating and re-generating the classifier for the API is still semi-solved. Currently, to re-generate the classifier -

- We run a couple of SQL queries to get our data out as CSVs.

- Run a script on the data which pre-processes it for training.

- Run another python script which trains our model.

- Copy-paste the model into the API folder which uses this as a backend to service its requests.

All of the above steps are well-documented and are verifiably reproducable using code snippets as detailed in this repo.

This process is to be replaced by a pipeline which automates all these steps, hopefully limiting the need of manual intervention.

Future work

We are far from finished on this! Not only are we chasing better classifier performance and a fluider architecture; we started off with the lofty goal of making a high-quality, truly open-source credit-card fraud detection system and we intend to make it happen.

While the indecipherability of the decision making process of machine learning models is considered a con, here it helps in obfuscating the same process from fraudsters - even though they might have the code readily available!

Currently, we have 3 major tasks on our plate -

- Integrate with WMF transaction workflow. Seeing how our model performs on new data would help us make sure that our approach is “correct” and it works.

- Developing a pipeline which automates the task of classifier generation from data.

- De-coupling the API and the pipeline from our data schema so that the code can be used and tested by other non-profits/organizations wanting to incorporate this into their in-house fraud detection service.

Acknowledgements

This post and this work wouldn’t have been possible without help and continuous intervention from Adam Wight, Eileen McNaughton and the rest of WMF fr-tech!